Monday, November 26, 2012. The array of I.V. bags dripping into my vein includes saline, painkiller, and three or four antibiotics. I’m not aware of much of this beyond the rich sensation that I’m lying in a bed instead of sitting in the wheelchair where I waited for two hours on an extra busy afternoon at Kona Community Hospital’s Emergency Room.

The nurse has covered me with a warm blanket, but my teeth are still chattering, and my body is shaking with fever. The nurse also told my wife, Laurel, to go home and pack an overnight bag. Laurel explains to me that Michael Dunlap, the doctor in charge of E.R., took one look at the nasty wound on my left ankle that has my whole lower leg glowing bright lobster red, and passed on his fears to her. He’s called for a medevac to fly us from Kona to a hospital in Honolulu. He said the spreading wound has reached the life-threatening stage.

The source of all this mayhem was nothing more than a delicate little cut not much more than a quarter inch long, which made the unfortunate choice of getting infected by some vicious streptococcus bacteria. Strep is never good, but when it finds a weak spot undermined by poor circulation, trouble is guaranteed even when the patient’s healing spirit is willing.

Forty minutes later, two paramedics in khaki show up with a gurney.

“We’re ready to go now, sir,” says the shorter man. “I’m Craig, and this is Matt. We’re going to take you to the airport.”

Craig and Matt pick up the gurney and slide it home into the rear of the ambulance. Craig climbs in next to me and locks my moveable bed into place.

“How you doin’?” he asks.

“Never this bad before,” I answer. “From my toes to my knee, my left leg feels like it’s on fire.”

The engine is already running. Matt turns on the lights and the siren and pulls out of the parking lot north on Highway 11. The siren cries through Kealakekua, and Craig says, “We’re due at the airport about the same time as the plane, but just in case he’s early.”

Matt pulls off the main airport drive and stops. Craig swings the back door open and climbs out. Then I see Laurel silhouetted in the open door. She’s put on a jacket, even though it’s plenty warm in North Kona.

“Move to the front,” says Craig, taking her duffle bag. She slides up the seat facing me and gives me a smile, touching my cheek with her hand.

“Are you okay?”

“No. But better now that you’re here.”

Matt pulls ahead to the gate and waves at the guard. The gate dings open, and we drive out onto the tarmac.

“Our bird has landed,” announces Craig.

*

Dr. Nicolas Nelken is the vascular surgeon who’s going to operate on the blood vessels in my left leg to create enough flow to heal the wound on my ankle. On Thursday, the 29th, he comes into the room and pulls up a chair. He wears a ponytail and a Van Dyke beard and has a professional bearing that makes his look work.

I’m very happy to be talking to him about moving forward. It’s taken three days of antibiotics to bring me to the point where I can speak coherently, and the painkiller level can be reduced.

He crosses his long legs and says, “We have two ways to go on this. I’ve looked at the ultrasounds and decided that your femoral artery is the problem. It looks like what should be a powerful torch is behaving more like a candle. From your groin to your knee, we have blockage. Surprisingly, the three smaller arteries in your lower leg look pretty good.”

He stands up and looks down at my leg. “I want to do an angiogram to get a better look at that large artery. If it looks good enough, we can perform an angioplasty and open it enough to work well. If it’s blocked too severely, we’ll find a good vein and bypass the femoral to get your blood moving down your leg.

“Any questions?”

“When do you think you’ll be doing the surgery?”

“We’re looking at Tuesday, the 4th. Are you free then?” he asks, grinning.

“I’ll have to check my calendar, but I think I can make time,” I answer, smiling back.

I need to stop right here to fill you in a little on my medical history, so you’ll understand why I have to joke about this.

I came down with Type 1 diabetes when I was in my mid-twenties. My dad and my sister had both died of it, so I took it very seriously. In spite of keeping good control, the diabetes hit my eyes with diabetic retinopathy, but thanks to an excellent program at the University of Washington Medical Center, I got laser treatments that saved them. In the late 90s, the diabetes knocked out my kidneys, and I had to go on dialysis. It turns out, I was one of the very fortunate ones—in 2002, UCLA gave me a double transplant, not just a kidney, but also a pancreas, so I lost the diabetes after 33 years. I’ll take anti-rejection drugs for the rest of my life, but what a trade-off.

A few days later, I’m just about to drop off asleep when the door opens again, and Dr. Nelken, my surgeon, comes in. He’s wearing his blue scrubs.

“Hi, doctor. Looks like you’re having a busy day.”

“Right you are. Surgery is not a nice, neat job where things come in measured doses.”

He crosses to my bed and says, “Let’s take a look at your and my handiwork,” and pulls the blanket from my leg. “Looks very clean, but I had some excellent help. How’s the pain?”

“Nothing much, I’m happy to say.”

“If it gets worse, let the nurse know right away. You shouldn’t put up with pain. It just gets in the way of healing.”

“So did you do the angioplasty?”

“I told you that was a possibility, but when I got in there, it was obvious that it would have to be a bypass, which fortunately went very well. We knew that there was blockage in your femoral artery. That artery, in fact, is harder than a pencil. Completely blocked, thanks to diabetes and years of smoking. It’s fortunate you quit smoking when you did, or you wouldn’t be alive today.”

He pulls the blanket back over my leg and says, “How do you like the ingenious bandage? It not only protects, it heals, as well. We’ll take it off in five days, and your sutures will heal and disappear on their own. I can see that the bypass on your right leg was a lot more complicated.”

*

Viki Lai Hipp is a wound nurse. Her official title is Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurse.

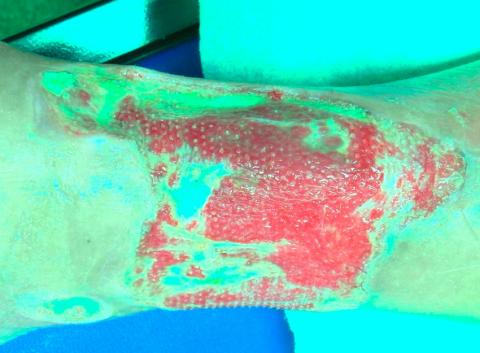

The first time I met her, she arrived with one of the doctors to look at the wound, now that the vascular surgery team had performed a femoral bypass to give me the blood flow I needed to heal. After unwrapping the bandages and gauze, she studied the open wound that covered about fifteen square inches of my lower leg and told me they were going to use something to help it heal. Honey!

Reflecting back, I know that even in ancient times, honey was used for its medicinal properties. And today, she was applying honey over my leg. Not just any honey, but leptospermum honey, honey from bees feeding on the flowers of the manuka, or New Zealand tea tree, which I find out is famous for its ability to work against many bacteria.

As she spreads it on, its soothing feel relaxes me. She covers it securely, wraps it in gauze and says, “We’ll let it work for two days, then unwrap it.”

Two days later, everyone who looks at the results of the honey is impressed. After cleaning the honey off and looking at the improvements, she feels that a second treatment of honey is called for.

In two more days, she cleans off the honey and tells me about the next step they are recommending. Honey can’t hold a candle to the exotic nature of this treatment. For the squeamish, it’s called MDT. In plain words, it’s maggot debridement therapy. Still used in only a few places, it’s one of the most effective treatments for infected wounds, especially for diabetics. And, even though I haven’t had diabetes for eleven years thanks to my pancreas transplant, I still suffer from what diabetes did to me.

An Irvine, California company called Monarch produces disinfected phaenicia sericata larvae, sterile common green bottle fly larvae that are administered to the wound in small nets of between one and two hundred. Maggots are not interested in healthy tissue, so they only eat the diseased areas in their surroundings. They are sterile, so they bring nothing foul with them. When they’re applied, they are about the size of the tip of a ballpoint pen, but kind of transparent, almost like tiny pearls.

They’re wrapped securely in a nylon sleeve that allows them to breathe, and then further wrapped in thick gauze to help control the increased seeping from the wound. After two days and one gauze changing, my leg is unwrapped, and the maggots wet-vac’d and disposed of. They’ve grown to the size of fuzzy grains of rice, and the wound is much freer of necrotic tissue.

Viki decides that we’ll probably need to clean the wound with MDT four times. Six days later, Viki and Dr. Philip Bruno, an infectious disease specialist, are happy with the results and recommend that I start using a wound vac. This machine is connected to a sponge covering the wound. It draws seepage from the wound and encourages blood flow in the area and is attached by a plastic tube to a power source the size of a small vacuum cleaner that sits by my bed.

For four days, I’m leashed to the machine, and when I go for my daily walks throughout the hospital, I attach the vacuum to my walker, which groans at the extra weight. Laurel and I are relieved when we hear that they’ll be providing me with a home wound vac and sending me home on December 21st. We won’t have to celebrate Christmas in the hospital!

It’s an interesting feeling, saying goodbye to people that I know so well, yet hardly know at all. I know nothing of their lives aside from the fact that they are good with a scalpel, or administering painkiller, or bringing me an extra blanket. And they don’t really know anything of me. They’ve seen me at my worst, howling with pain, vomiting, fouling my bed. And they’ve seen me heal, and rejoiced in that healing. But they’ve never seen me at my best. They aren’t familiar with the way I live. My likes or my dislikes. My taste in music or food.

As I shake their hands and look in their eyes, smiling with congratulations at my leaving the hospital, I know that I will probably never see them again. I want to hold them close and not say goodbye. After all, they’ve saved my life. At the very least, my leg.