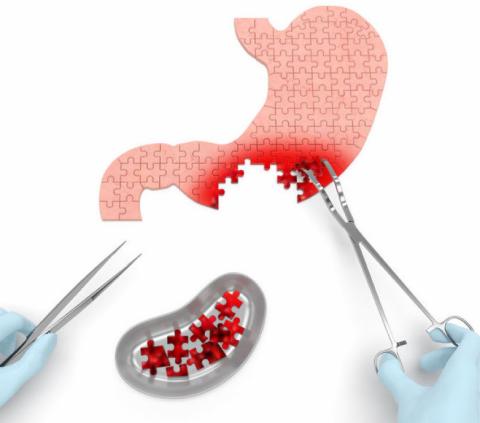

Partial gastrectomy surgery (removing a portion of the stomach) isn’t always for weight reduction. Sometimes we’re just a mess inside, frequently from ulcers. It was self-induced damage in my case.

About the self-induced part, I whipped myself unmercifully for creating the devastation inside. Long years of self-abuse from alcoholism brought my body to the brink with severe internal scars from my battle with drinking. Fortunately, I had 15 years sobriety by the time I needed the surgery, so the damage stopped there. But psychological self-flagellation was normal for me. It was kind of a sport to see how badly I could batter myself about past misbehaviors.

The evolution to my partial gastrectomy started in March, 2004. My Dad was dying, at home, where he wanted to be, with 24 hour nursing care and his family surrounding him. During the three years of his gradual debilitation, I was one of the siblings still in town, willing and able to help. In the meantime, my usual habit to ignore the hell out of whatever ailed me started a downward spiral to “death by starvation”. I didn’t intend or want to die. I just practiced denial like an art form. By the time the surgery was imminent; I weighed 89 lbs., felt bewildered and sick, and could not fathom how this happened. The weight loss was caused by non-bulimic, but just as prolific, throwing up, along with avoiding the pain caused by eating by just not doing it.

The week Dad passed away, all my siblings were in town. The strained atmosphere of a grieving family drifting in and out of the house hung like a cloud. Some of us entrenched ourselves there during that last week. My youngest sister and I stayed by the bed of my father as he passed on. I wanted to be there, though my body rioted against that decision. In his last hour, I was in severe pain, doing my best to ignore it. In the preceding days, I was just annoyed at the intense burning under my diaphragm. Later, I found out that was an “acid wash” coming up from my stomach, serious reflux. I didn’t know what “reflux” was back then. Horrific timing, that’s all I knew!

On March 17, 2004 we buried Dad during a snowstorm. (“Real funny, Dad”, I thought, trudging my high heels through the snowy cemetery for graveside service. “Snow on St. Patrick’s day. Hilarious.”) That day, I threw up for an extended period. From heartache and exhaustion, right? The reality was my stomach was suffocating. I casually mentioned my constant heaving to one of my sisters, who railroaded me into the doctor the next day.

The bloody part of my throwing up distressed my primary care doctor. He’s super laid-back. The alarm on his face stopped my “deal with it myself” nonsense dead in its tracks. I figured I better follow what he suggested. He had saved my ignorant, denial-ridden self pretty often. The nurses scheduled my first ever endoscopy that week.

My gastrointestinal specialist showed me the ghastly photograph from the endoscope. Explanation was unnecessary. I studied the sharp image of a tiny hole where food had trickled through, surrounded by discolored scar tissue (certainly not a healthy pink), and listened to his plan. Minutes later, the good doctor was on the phone scheduling a surgical consult with the surgeon who had taken care of his own stomach ailment years before. Why I merited this privilege, I don’t know, but I remain grateful to this day.

My mom started crying, right there at the schedule desk. “Why can’t it be sooner?” she whimpered. My own denial whispered to me, “Piece of cake, four weeks.” I didn’t say that out loud. Mom’s sadness and paranoia said, “Someone else is going to die.” She didn’t say that out loud either, but I knew it was in her heart.

Fear followed me like a thundercloud, but not about the surgery. Handling the details of recovery, like no income for weeks on end, was no small matter. It astonished me that the operation wasn’t scary, considering they were filleting me like a fish! I never thought about dying, though. I scurried about arranging for people to take care of pets, wrapping up office duties, putting off clients in the horse training/riding instruction business, paying bills, etc. The busier I got, the sicker I got.

The toughest thing? Dealing with others’ fears. I spent the hour before I left for surgery trying to calm the fears of my beloved husband and my Mom. The week before, all of my seven siblings had contacted me. My brother let me know of Mom’s paranoia about losing another person in her life and gave me a directive: “She can’t take someone else dying. So don’t.” I promised not to.

I don’t remember post-op, but I do remember in the hospital room my eyes popping open to my youngest sister leaning over me, alarm plastered on her face. I heard myself weeping from pain. I was assured by the nurse I had a hefty dose of morphine in me. Let me mention for the record, I almost never cry from physical pain, even with a history of many broken bones. Maybe five weep-fests in my life, three of them from passing kidney stones. Even with kidney stones, I knew the standard Demerol and Morphine mix did not do squat for someone with my peculiar high pain tolerance.

My sister may have remembered this. She climbed all over the staff to switch medications the moment I woke up sobbing. I could hear her tromping up and down the hallway, “discussing” loudly what the staff needed to do for me. A Dilaudid pump appeared in what seemed like very short order. Though I did not approve of her approach, my sister assured that my recovery was on its way! She left me late that night, well satisfied she had done her best to help me.

The next morning, I woke up to my mother leaning over my bed, counting the staples (28) in my belly. They had cut me sternum to navel. It fascinated her to see the incision and the new way of “fastening” it. I would have laughed if that wouldn’t have torn me open. She visited daily and I kept asking her “Aren’t you tired since you, you know… everything with Dad?” “No, no, I’ll just stay a little, maybe till dinner.” Maybe she reasoned, “I’ll stay just until I make sure you don’t die.”

I was not sure if it was partial gastrectomy post-surgery protocol, my fragile underweight condition, or something else, but in this day and age, when insurance companies boot your butt out of the hospital in a heartbeat (no pun intended), I was pretty alarmed by the fifth day in. Eventually, a nurse explained it depended mostly on the fluid return from the NG (nasogastric) tube. “If the color was right,” she said. I watched the fluid like a hawk from then on, as if I could do anything to change it.

I wish I could say it was all just peachy after my discharge. Both my bosses at the office and the horse farm job wanted me back as soon as I could sit up. My own workaholism drove me back to the grind in about five weeks and I was supposed to be off work six to eight weeks. Not the smartest decision, and my body paid me back: It took me over a year to get above 90 lbs. and regain my strength. That was a decade ago and I still maintain a physically active lifestyle. Most people don’t know I had a major surgery.

I hope anyone reading this can begin to understand how denial can easily destroy you

The lesson is obvious: listen to my body talk (and sometimes scream.)