I had ten hours left. I was fourteen years old and certain of this as if it were a known fact. The following morning, they would wheel me into the operating room, cut me open, and in the process, they would kill me.

And yet there was something beautiful about this moment. On the cot beside my bed, my mother’s breathing was quiet and regular. I walked slowly across the floor toward the window, the tiles icy beneath my feet. On the other side of the glass, the Bronx danced alive and summery. It was early July, one of those nights where the moon is a giant smoky orange disc that seems to hover just above the tops of buildings. On the street, tiny figures in tank tops and shorts crossed back and forth. Even as I stood in an air-conditioned freeze, holding my arms tight against my body, my skin prickly with goose bumps, I could feel the freedom of that heat, that humidity, that energy.

Convinced though I was that this was the last night of my life, somehow I wasn’t afraid. I’d spent most of the last two years fearing these very moments but suddenly I was calm and completely ready.

~~~

I was twelve when I’d first heard a doctor utter the word.

“Scoliosis,” my pediatrician told my mother, “It’s not serious right now, but she’s growing fast. We should keep an eye on it.”

It didn’t sound too bad. And in retrospect, it wasn’t – just a matter of a few orthopedist visits, some x-rays, and a chiropractor appointment every Tuesday and Thursday after school.

All I knew was that I didn’t want to end up like my best friend, Jessica.[*] One year older than me, she’d strangely gotten diagnosed with the same rare condition. Hers, however, had progressed quickly. She’d worn a plastic back brace for a year which had seemed not to help at all, and now her doctor was talking surgery. I thought of Jessica and made sure never to miss a chiropractor appointment. I did the exercises he gave me every night. I prayed.

Please God, I would whisper in my bed, please don’t let my curvatures go past twenty degrees.

Twenty was, after all, the magic number. Twenty and forty, that is. Twenty degrees meant that bracing became inevitable. Forty degrees meant surgery.

But with all the prayer, with all the exercise and chiropractic manipulation, I watched the curves on the x-rays each month grow gradually more pronounced. Before I knew it, I was back in the orthopedist’s office listening to him explain the bracing procedure to my mother.

~~~

Mine was even worse than Jessica’s. Her brace was almost entirely plastic and ended below her chest. Because of the positioning of my curvatures, mine was the older style of brace – a Milwaukee brace with metal bars that extended up over my shoulders. I stared at it sitting in the middle of the room. It looked like a cage.

It got worse when I put it on. Most of my clothing didn’t fit and those that did fit didn’t seem to adequately hide the metal bars. I glanced at my reflection in the mirror. My body looked utterly unfeminine, almost like a football player’s.

And here’s the thing: I still had to go to school the next day. I was in seventh grade and already unsure of myself and awkward. That morning, I buttoned up a too-big blouse to the top button and tugged it over the brace, trying to hide it as best I could.

My efforts were in vain. There was no hiding this thing. As I walked on to the bus the next morning and then through the hallways, I felt all the eyes upon me, watched my classmates whisper and quickly look away. I was a monster. I was hideous.

Looking back, I know I could have handled this differently. I knew two other girls who had to wear braces – Jessica and another friend. Neither of them seemed to wear it with as much shame as I did. I excused my insecurity with the explanation that theirs were the smaller, less bulky versions of the brace – clearly less embarrassing, less ugly.

And then there was the Judy Blume novel, Deenie, about a teenage girl who wore the same brace I wore. She managed to feel good about herself, even to attract a boyfriend. But again, that was fictional. Surely, I believed, I could never be that confident.

So I spent two years with my eyes down, wearing ugly clothing, and hiding whenever I could. The brace was physically painful, too. It jabbed and poked into my sides; it rubbed against my skin; it gave me rashes during the humid summer months. But the worst part of it for me was the way it made me different, made me weird.

“Why does that girl look funny?”

I heard this almost anywhere I went, the children staring curiously at my lumpy, large figure, and then confusedly up at their parents. The adults were almost worse. A quick glance and then a forced stare away from me as if I was too horrible to look at.

The worst still, though, were the metal detectors. Airports and museums became personal torture chambers for me and I would mentally prepare myself for the loud beeping and the subsequent stares as the security guards traced the contours of my brace with their squealing wands.

And of course, there were the boys. Most just seemed not to notice me. But then there were the select few who were cruel in a way that only middle schoolers are.

“Oh yeah, well you kissed Rachel Adler,” Steven yelled to Lee, as I sat right in front of him, the tone in his voice implying that this was the unthinkable, the ultimate insult.

~~~

Still, where my two other friends “cheated” on occasion, taking a few days off from the brace now and again, I never did. The brace was going to hold my spine in place, was going to prevent my needing surgery, which I was determined to do. I took it off to shower, to do my exercises, and that was it. Though I hated the metal and the plastic so much, they began to feel just like another part of my body.

And yet every few months, I would go to the orthopedist and watch the image of my spine grow increasingly curved, the numbers creeping their way up to 40. My prayers grew more desperate, more pleading. Please God, please make my scoliosis go away. I’ll do anything. I’ll be so good. Just please make it disappear.

It didn’t help. About a year and a half after I had started wearing the brace, I found myself sitting on the examination table, watching as the doctor wrote the number “42”on the side of the x-ray. Even as he opened his mouth to speak the words, I knew what was coming.

“We need to talk about surgery.”

Over the next few months, I kept a brave face for the world but inside I was worrying, crying, despairing. How could this have happened? I’d worn my brace religiously, I’d done everything I was supposed to do – and after it all, I would have to have the surgery anyway.

But there seemed no choice so I chose the date. I signed the papers. “A chance of paralysis,” it read, “Or death.” Those words stayed with me and I became certain I was going to die. I would look around the classroom at my friends and ponder the injustice of it all. They would get to live to become adults and my life would get cut short at fourteen.

I kept going anyway. Spent days in the hospital running on treadmills to test my lungs or sitting in a chair while my blood was being drawn. The days passed slowly through the end of school and 8th grade graduation, until suddenly there I was, in the hospital room the night before my surgery, standing at the window, inspired by life, and still somehow in that moment, unafraid of death. And there I was, being wheeled on a stretcher to the operating room the next morning.

“You’ll feel a sting and then you’ll fall asleep,” said the nurse, “Hold my hand, squeeze if it hurts.”

And then the girl that I was closed her eyes and fell asleep for the last time.

~~~~

“Wiggle your toes. Can you hear me, Rachel? If you can hear me, wiggle your toes.”

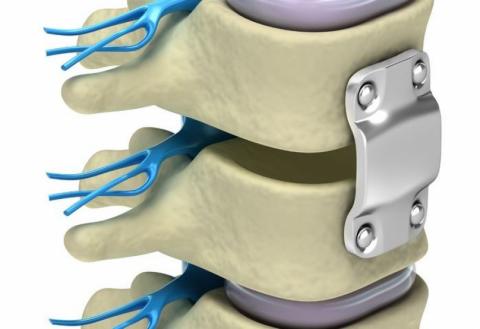

I did not die during those 10 hours. The surgery was long and complex but the surgeons knew what they were doing. They skillfully aligned my spine against two metal rods fused with bone from other parts of my body, and sewed me back up.

I awoke in the recovery room, hurting more that I had ever imagined possible and very much alive. The following week was lost in a cloud of morphine and pain. The days, doctors, visitors, therapists, vomit, and mood swings blended into each other. It was a week before I was fully conscious and two before I was walking. When I finally got home, my waking hours alternated between watching videos or television.

But in all of this suffering, I began to become aware of a slowly growing feeling of promise that had been absent from my life for so long. I was learning how to walk again, my body initially laboring to make it down the block and gradually making it further and further. I was rebuilding my muscles and the physical therapist would note how much stronger I’d become each week.

Most notably, though, I was feeling myself slowly becoming a new person. A person with hope for the future. A person, I noticed as I looked in the mirror, who might even be described as beautiful. There was, I’d begun to feel, something to my belief that I would die on the operating table. I wasn’t the same person I’d been for the past few years; it was almost as if in reconstructing my spine, my surgeon had reconstructed my self as well. I started school the following September as this new person, bursting with confidence, bursting with a positive attitude.

Now, years later, I can look back and see that it wasn’t so simple as to say that the surgery changed me. Rather, it was the whole experience – the bracing, the lead-up to the surgery, the belief that I was going to die on the operating table, the recovery itself. There’s something about overcoming a severe medical issue at such a young age – about having to face your worst fears and your own mortality in your youth, about spending childhood years as an object of spectacle and disgust. As I continued into my adulthood, I took the memories of these experiences with me and held them close, even as I embraced my new person they had helped me become.

I’ve continued to experience medical issues. I was diagnosed with chiari malformation and syringomyelia in my 20s and broke my hip at 30 – and life has presented me with a host of other, non-medical tribulations. But here’s the thing: I have learned that the unexpected is okay, even when it is daunting or upsetting. In the process of living with a back brace, of facing and going through the subsequent surgery, I learned how to be myself, how to love myself, and how to remain strong in myself no matter what. And with that knowledge I know I am capable of conquering these challenges, that no pain or humiliation can stop me. That I may not be able to control what happens to me, but I can control how I will respond – and, at the end of the day, that is all that matters.

.