Watching my grandmother die was like watching a baseball game go into its fourteenth inning with no clear winner. By the bottom of the twelfth we were all ready to get up and walk out. The onset was slow, a few misplaced items, a forgotten appointment, a small fender bender on her way to church. It took months, maybe even years, to finally progress to a diagnosis, but once she was labeled, identified, classified as a seventy year old woman with dementia, the end came quickly.

"Cookie is yelling again." My coworker mumbles as she chomps her sugarless gum. We work at a local TV station, doing grunt work for six dollars an hour. I'm twenty-one and fresh out of college, it's a good start. I stand up and look over the grey cubicle wall that surrounds me. Cookie, our middle aged receptionist, is holding the phone in one hand and frantically looking around for someone to answer her cries.

"Does anyone have a grandmother named Geri?" She yells again. I look around and sit back into my squeaky maroon chair, the one I spend nine hours a day in. Suddenly it hits me, and I pop back up.

"I do!" I yell.

"I'm transferring a call back to you." She yells. My heart starts to pound.

My phone rings for a millisecond and I grab the dirty off-white receiver.

"Hello?"

"Hi. I have your Grandmother here." Oh my God! The panic starts to set in. She's been kidnapped!

"Who is this and what do you want..." I ask suspiciously.

"My name is Bill Sherman, I live on River Street." River street… I'm writing all of this down, this is too easy. "I poured some fresh sidewalks yesterday and your grandmother fell on them about ten minutes ago. The concrete must have still been wet." He says.

"Oh...Is she okay?" My voice starts to crack as I realize the type of call this is. My grandmother is not being held for ransom, she's hurt, and she needs ...me?

"It's bad honey. I called an ambulance, they are on their way."

"Did you call my father?" My father, her oldest son, the one who she depends on, who takes care of these types of situations. My hands are shaking, I'm new at this.

"Honey," Bill Sherman says, "She doesn't know her last name. All she knows is that her name is Geri and she has a granddaughter who works at channel 22.” Through the phone I hear the sirens approaching.

Suddenly a rush of adrenaline jolts me into action.

"Listen Bill," I say with authority, "Tell her I will be right there. Tell her I am calling her son, Sammy, and we will all be right there. Make sure you tell her she will be okay."

But she wasn't. She hadn't been okay, but none of us could admit it. She lost five hundred dollars last spring without even leaving the house. My father and I scoured the whole house for two hours before finding it in her wallet. She must have not realized. I do those kinds of things all the time. My father shrugged it off. Then, three or four months later after three fender benders within weeks of each other, it was decided the car had to go. No more driving. She's getting older, the reflexes tend to slow down, again, we dismissed it. Now the wandering was starting. A frantic neighbor in the middle of the night, calling my father to tell him that Grandma was walking down the street in her nightgown. It must be the medication, maybe it's not agreeing with her. Maybe she was sleepwalking. Maybe it was just an isolated incident. My father let her off with a warning, no more leaving the house alone.

Later that day, after the fall, as I stood with my father looking at my grandmother's frail seventy year old frame, clear tubes going in and out of her veins, carrying clear and colored liquids back and forth from her small body to large hissing machine, the reality set in. Her eyes remain closed, her forehead adorned with dry blood, her seventy year old knees skinned young again under a beige hospital gown, her lips crisp with dry skin... She was an old wrinkled mummy concealing the plump, gentle, Polish woman I grew up with.

In the days that followed we did a lot of waiting. We waited for her to wake up, we waited for the doctors to tell us why she wouldn't, we waited for her to remember us when she did open her eyes, we waited for her to give us any sign of hope that she was getting better. I watched my father, on the verge of becoming an orphan, struggling with the decision he had been putting off for weeks. A home will be the end of her. She will die there.

On the day they brought her to the Alzheimer's specialized care facility, my sister and I arrived a few hours ahead of the others to decorate Grandma's room and make sure it was as comfortable as possible. We hung the only known picture of her and my grandfather as young newlyweds over the large hospital bed, we brought her rocking chair, the one she would rock us on as children and tell us stories of being a dancer in the 50's, and we filled the plain brown chest of drawers with some of her clothes, most of which we had to buy brand new since she had lost so much weight in recent months.

A prison for the elderly. That's what this place was. Because of the tendency of the patients, who all suffered from either Dementia or Alzheimer's, to wander, the facility was on lockdown at all times. Cards and badges were needed to go from one room to the next. In the hallways sat random women, some staring into space, some crying, most just staring at my sister and me, maybe envying our youth, or maybe remembering a time when they too would have cringed at a place like this.

The first day was rough. My father cried harder than I had ever seen him cry before. My grandmother was a child, clinging to his leg, pleading with him to realize the mistake he was making. In her eyes he saw his mother, the same woman who loved him and kept him safe for the last fifty years, not the irrational patient the doctors proclaimed her to be. One of the cruelest aspects of Alzheimer's and Dementia is that the victim is completely unaware of its grasp. I imagine that in those moments of begging and pleading for her freedom, my grandmother was sane and had her wits about her. I imagine that she felt terrified and betrayed, not just confused and disoriented as the doctor's described her. It's hard to imagine my family not being able to trust what comes out of my mouth, not willing to listen and accept that I know what I'm saying.

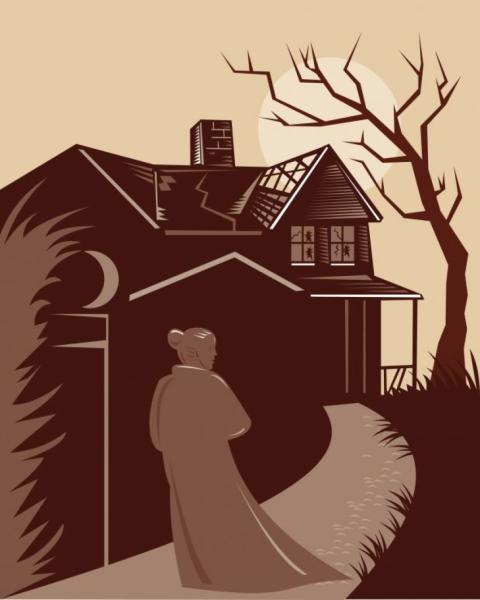

My grandmother died in that home, just as my father knew she would. I'm ashamed to admit that I didn't see her as much as I should have. It was painful to watch her disintegrate, and I think part of me wanted her to remain my plump polish grandma, the one whose spaghetti sauce recipe is still unknown, and has never been copied. The grandma who dragged us to church every Sunday, but always made up for it with a banana split after, the grandma who filled a million brag books with our pictures and showed us off to everyone, brag books that I have inherited, and still keep exactly the way she left them. I live in her house now, raising my children whom she never met, and everyday I think about her. I smell her sauce cooking or hear her laugh very faintly, and I know she's here, and that she forgives all of us.