“If you don’t straighten your leg, I am going to hit you with this ruler.” I had no reason to doubt his sincerity. He held that twelve-inch wooden ruler with conviction, slightly up in the air and at the ready for a downswing onto my right thigh.

Try as I might, I could not move my knee at all. I sat on the examination table with my legs dangling over the edge, beginning to sob because I didn’t know what else to do. I didn’t want to get hit, but I couldn’t do what he asked unless I grabbed my right calf with my own hands and lifted until the joint was straight. Surely that wasn’t what he meant….

My blubbering, I guess, convinced him, and he put the ruler down. It had been one week since the cylinder cast came off. November 21st. Dx: FU Avulsion tib tub. F.U. avulsion indeed. After the appointment, this doctor told my parents I would never walk again. They decided not to tell me that. Without physical therapy or surgery and with nothing but an x-ray and I presume a prescription for ibuprofen (that is the painkiller Black people most often seem prescribed), the clinic sent me on my way.

Oh, you didn’t know I am Black. Well, technically (if there are technicalities to racial designations), I am descended from more White people than BIPOC, but at the time of my injury I had been living in Hawai’i for almost a year and was tanned into Blackness. Honestly, you don’t think a doctor would threaten to hit an eleven-year-old White girl, do you?

I would later name my right knee Judas, I hope not at all because that clinician thought it should be beaten. In the beginning, though, my knee was just a knee. It hurt, but it wasn’t something that caused me endless frustration. It worked fairly well I thought. I kept using it … that is until I couldn’t.

I remember sitting down on a curb as a child during a family walk having complained of the pain to the point of nonsense. My mother asked the family physician about it. “She just wants to be picked up and carried,” he assured her. What child makes up that her knee hurts? It wasn’t the first time a doctor made up something outlandish explaining symptoms to my parents. When I contracted chickenpox from the neighbor’s kids, the pediatrician asserted that I had “foot and mouth disease.” Mom transferred care. With knee pain as the only reported symptom, though, the poor medical judgment was not as clear I guess.

The pain continued, and when I was nine-years-old and staying with relatives while my parents traveled Europe, I was writhing in anguish when my RN aunt recommended over-the-phone to my uncle who was babysitting that he put me in a hot bath and rub my legs. I remember his face, so worried. The intervention was such relief for me. Uncle Bob became my favorite person in the world. There was actually something that could be done to help me, and he was the one to do it.

Two years later, Judas had finally had enough. I was playing basketball in the park when I dribbled down the court, stopped to pass the ball, watched my teammate score, and found I couldn’t walk. I stood on the court alone, my peers running in celebration back to school so as not to overstay recess. I looked around hoping to catch the eye of an adult. Not finding one, I wondered how I was going to traverse a quarter mile down a flight of stairs and across a baseball field to Hokulani Elementary. I couldn’t lift my right foot off of the ground without my knee feeling like it was tearing apart. So, I grabbed the top of my sock, pulled upward to keep my knee together, and began a journey more painful than when my surgeon years later began cauterizing a laceration after the anesthetic wore off.

When I finally arrived at Hokulani’s medical office, the nurse placed my foot on a chair and set an icepack on my knee which sent me howling. I lifted my foot up with one hand while holding under my knee with the other and rested my heel on the floor straight legged. Eventually my mother picked me up and took me to the emergency room for x-rays and little treatment at first beyond RICE (or rather RIE; I don’t think compression was in the mix), then a visit to the clinic for a knee cage, then a cylinder cast. That cast certainly made mobility easier although it was the reason I was not allowed to compete for the Presidential Physical Fitness Award even though I told the judges I could do it. Yeah, I’m still sour about it.

With the injury came crutches which a racist classmate tried to kick out from under me (why keep calling me the n-word when you can hurt me physically?). Perhaps with that as motivation, within the first week in the cylinder cast, I learned how to get around without any assisting devices.

Once the cast came off, my leg just collapsed underneath me. I could not walk. My peers thought it was hilarious; me falling to the floor trying to get from one classroom to another never got old. Eventually I taught myself how to keep my foot pivoted outward so that my right leg could be used more like a cane. My right calf and quad muscles remain considerably atrophied compared to the left, but as the years passed I taught myself how to work my knee more like a normal one. There remains a particular angle that is inoperative, and I failed to compensate during a few pivotal moments: swinging a home run during a pickup softball game, doing lunges while training for my collegiate track and field team, navigating an icy patch in a mall parking lot, jumping from a dock onto a boat. I wonder if that little boy would still laugh.

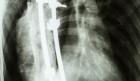

What is visible now is a kneecap that rubs against my femur sans cartilage. An orthopedic surgeon a few years ago recommended a partial replacement and mused that what I actually experienced when I was eleven was a knee dislocation. Why? I suspect the story about not being able to straighten my knee wasn’t quite heard. This surgeon interrogated me when I said “no,” that it was an avulsion of the tibial tubercle. “How do you know?” “I’m relying upon the diagnosis in the clinical records that I provided you,” I answered.

Instead, the first and only surgery Judas has ever had is a scope long after date of injury, after I entered junior high, graduated high school, then college, then law school, after my career as a lawyer, my career acting, and six years into my career in academia. At the time, I was open to the recommendation of “TTO with MACI,” explained in laymen’s terms that it meant breaking my leg and re-setting it with a flourish of transplanted cartilage. The scope on its own damaged my knee further but in a new area, and another surgeon told me TTO-MACI should never have been considered anyway given what is written: having no cartilage is contraindication.

Regardless, when I asked the scope surgeon about the development of this new painful crunchy grinding that shows up in MRI simply as “worse” than before, he answered, “I did that,” but offered no further explanation. Does not boost confidence … as neither did him initially marking the wrong knee for surgery.

Meanwhile, in the month before the scope, I decided I must break and set (a theme, I guess) as many world records in indoor rowing as I might because I didn’t know what would become of Judas afterward. For my birthday – on my birthday – I racked up eighteen of them, adding to the dozens I had accumulated over the years having switched to rowing after Judas decided running, tennis, and every other high impact sport was out of the question. All of my rowing accomplishments hurt and create, too, a pain in my right hip because of the warped angle of my foot I myself designed into permanence when I was eleven. Pain is the price I know must be paid, the cost Judas demands at all times.

This pain experienced until my scope operated like gravity, just a challenging fact of my life on Earth. It wasn’t until I was prescribed Percocet after surgery that I realized I could have been suffering less for all of these decades. How enraging. It created pain that was now terrorizing. After finally convincing my PCP that I should see a pain specialist, that doctor proclaimed when we first met, “So I understand that you have been experiencing knee pain for a couple of years” and left me with, as Wanda Sykes calls it, ibufuckinprofen.

I replay my childhood and wish I knew anything then about physical therapy and rehabilitation. But why would a child be well-versed in such things? No idea, but it doesn’t stop me from dreaming. I read studies of tibial tubercle avulsions with such envy for those who recovered and the medical treatment they received. What would it have been like to have a doctor who didn’t think I was a child malingerer? The elevation of my patella that my initial treaters discounted remains, a residual of something I surmise was serious that continues to be disregarded, perhaps related to the periodic collapses. It’s not Judas’s fault of course. These are how injury is compounded, how less than stellar responses damage an entire life. But this story is beyond the broken places. It’s a love story.

After all, what else could keep pressing us onward?