"What are you, stupid or something?"

I was in line at the supermarket. The cashier, who didn't seem to have cerebral palsy but was clearly somewhat limited, was taking just forever to make my change. He blushed red with embarrassment as my words cut into him, fumbling with bills and coins as he struggled to find the right combination.

Customers on the growing line behind me alternatively nodded in agreement with me and disapproval of him. Some sighed deeply, others folded their arms with impatience. What the hell was wrong with this guy?

Hate me yet? You should. Thankfully, the scene above was fiction. I never said that and, if I had, the reactions of others would have been far different. That's a good thing; a sign of societal progress in an ever-widening war against bigotry.

What did happen and continues to happen quite frequently, is this: As usual, I am struggling to read the menu, perched high on the wall behind the order counter. I knew I wanted soup and a salad, but the multitude of choices was paralyzing. But this wasn't lunch-hour indecisiveness; I simply couldn't see what was offered.

"What are you," a hungry fellow luncher quipped, rolling her eyes, "blind or something?" The man behind her, as well as the cashier, didn't bat an eye as they waited, impatiently, for the idiot in the room—me, to finalize his food order.

"Actually yes," I replied, in well-rehearsed monotone. "I have a visual disability." Luckily, she hadn't ordered her meal yet, because she might have choked on it. It's a safe bet that she'd used that line plenty of times, but never received so humiliating an answer. My truth was her life lesson.

Me, Myself and Eyesight

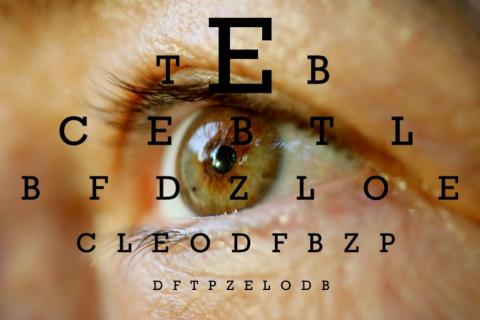

When I was 23, I started losing my eyesight. Over a two-year period, my once 20/20 acuity dipped to 20/30, 20/40, 20/50. Meanwhile, visual field tests revealed sizable blind spots in my central vision.

Doctors with increasingly long, intimidating titles took turns ordering bloodwork, CT scans, MRIs, even a spinal tap. The problem was clear—my optic nerve was deteriorating—but the reason was not. One said I probably had multiple sclerosis, another that I’d likely go mostly blind.

Fortunately, both were wrong. At 20/60 corrected with gaping bilateral blind spots, it suddenly stopped getting worse. That was 2004. Mercifully, since then my eyesight is largely unchanged; shoddy yet stable.

Officially, my diagnosis-by-default is Dominant Optic Atrophy. A rare, often progressive disorder generally not detected until adolescence, DOA ranges in severity from asymptomatic (no measurable vision loss) to legal blindness.

In layman's terms, my vision sucks, and affects nearly everything I do. I hold books about six inches from my face, and sit just a few feet from my large, crystal-clear flat-screen television. As I type this, my computer screen is blown up to 220%. Despite these modern marvels, eyestrain headaches are frequent and head-splitting.

My visual disability is mentally taxing as well. Everything from sporting events to skiing is either significantly less enthralling or completely impossible. I don't recognize acquaintances until they're right in front of me and, at work, find myself fake-following PowerPoint presentations painstakingly prepared by clients who, I've generally realized, aren't worth clueing into my situational blindness.

My eyesight is limiting, alienating and, sometimes, downright scary. I've overcome a lot to get where I am in life.

I'm not looking for a medal. I just want to stop being mocked in public.

Eyesore

It is remarkable and inspiring how far society has come in accommodating, with understanding and respect, persons with limitations. We’ve made great strides toward better integrating, for example, folks in wheelchairs or with autism into mainstream society. The softening stigmas surrounding afflictions like PTSD and addiction also are promising.

We’ve also become more socially inclusive and enlightened. Transgendered people are openly gracing everything from the cover of fashion magazines to the U.S. military. The #MeToo movement has brought long-needed awareness to the widespread workplace sexual abuse and intimidation and, at colleges, young people are redefining identity roles and fighting ingrained, whitewashed privilege, cries of “snowflake!” be damned.

The common thread here is an uplifted definition of personhood. Everyone deserves to be treated equally, and with dignity.

That brings me back to the lunch line. Or the train station. Or any one of the myriad places where someone hurled a hurtful slur at being momentarily inconvenienced by my visual disability.

Would these same people tell a man in a wheelchair to “Get his crippled ass out of the way?” No. At least most of them wouldn’t.

Apparently, my disability’s invisibility—how ironic—lends license to insult. I’m able-bodied enough to comfortably mock in a society where such vitriol is increasingly, and rightly, admonished. I have no wheelchair, crutches, or guide dog; it’s a safe bet I’m not disabled, but rather a mere fool who can’t order his lunch, identify his train or read the fine print.

My invisible disability is not a vehicle for your need to feel superior. We all know what happens when you assume something, and what you don’t know can, and does hurt. Remember that next time someone takes a few extra seconds to order lunch.